#5 Soledad Sailing Challenge 2025 Corinth Channel and Gulf Stories

#5 Soledad Sailing Challenge 2025 Corinth Channel and Gulf Stories

August 27, 2025

Western Greece, Ionian Sea, somewhere offshore between Lefkada and Corfu

According to Greek mythology, when Odysseus arrived at Aeolia, the home of Aeolus, god of the winds, Aeolus welcomed him and his crew with warmth and hospitality.

In return, Odysseus entertained him with tales from his long and perilous journey.

As a token of gratitude, Aeolus gave Odysseus a bag containing all the winds—except for the gentle west wind that alone could carry him safely back to Ithaca.

And so, as fate would have it, that missing west wind was precisely why Odysseus wandered for so long before finally returning to his wife Penelope.

So far, we’ve sailed through every kind of wind and weather—everything, it seems, except the tailwind that would carry us straight home to Zadar.

Unlike Odysseus, we are not awaited in a castle tower by the calm and patient Penelope, but by my worried mom and dad at the dock in Uskok Sailing Club in Zadar, on their small sailboat. They keep calling, asking when we will arrive—but to that question, there is simply no answer.

However, if the forecasts are to be believed, then in a day or two a north wind should appear around Corfu, which will literally push us up the Italian coast of the Adriatic from where we will turn down to Vis.

If there is some eternal justice, then we have earned it because of what we went through in the Corinthian Gulf.

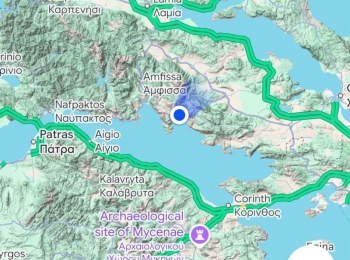

Crossing through Corinth during the golden hour was seasoned with music, a sunset, Instagram stories, and a glass of Campari. Drunk on both the moment and the aperitifs, we sailed straight through the VIP entrance to hell.

We felt the curse of Corinth on our own skin: it granted us four enchanting miles, only to lead us straight into the night and abandon us to the mercy of towering waves and a gale of 25–30 knots that struck wherever it pleased—most often straight into the bow.

We all knew there was no chance of covering so many miles without difficulties, but none of us expected such a trap on that short stretch.

Still, if it was objectively hard for us on Pero, then on Soledad it was nothing short of apocalyptic. The front hatch could not be closed properly and they were close to sinking.

Through the bow, literally without exaggeration, a ton of seawater poured in, and thanks to Başak’s composure they somehow managed to avert disaster—bailing bucket after bucket into the toilet and flushing it away.

The epilogue was that all the electrics failed, along with the batteries and both toilets that don't have manual pumps.

A few years ago, the whole world—and especially Croatia—watched with pride as Captain Jozo Glavić steered a massive cruise ship through the Corinth Canal. But from where I stand now, I can’t help but wonder how he even dared to take a passenger vessel full of “untrained” civilians into what feels, on the other side, like the very gates of hell.

The Corinth Canal had to wait 2,500 years to be completed, primarily because of the sheer scale of the project. But perhaps it is more romantic to believe that its long delay was also due, at least in part, to an ancient prophecy by Apollonius of Tyana, who foretold that those who dared to propose digging the canal would be struck by illness and death. Three Roman rulers—Julius Caesar, Nero, and Caligula—considered the idea, and all three met a violent end.

When Başak told us at 1 a.m., after hours of agony, that they had finally found an anchorage—with mooring buoys, no less—on the bay across from Corinth, we all felt a surge of relief, convinced that this dark episode of the Soledad Sailing Challenge had come to an end.

Of course, we couldn’t have been more wrong.

When we reached the so-called safe harbor, it turned out to be neither safe nor even a harbor at all. And the “buoy” was no buoy, but an improvised canister—half-decomposed, without so much as a handle to hold on to.

But, as troubles never come alone, the engine first began cutting out from air in the system, sending us drifting toward the rocks. Then, only moments later, the boat hook inexplicably snapped in half—the hook itself drifting off with the current before quickly sinking out of sight. After that, the only tool left for us to use to catch the buoy was Nikša's hands.

Luckily, it's a tool that never fails, and it didn't this time either. Nikša, with Özgür’s help—and mine too (I was holding the light)—tied us to the buoy.

When we finally came to a stop, I pulled soggy sandwich ingredients out of the soaked fridge, and we ate them while still wearing our life jackets.

Partly because of hunger and partly because of the trauma we’d just been through, it didn’t seem worthwhile to take the life jackets off.

Feridun’s life jacket turned out to be a particularly interesting addition to the already cataclysmic atmosphere because whenever he was at the helm, and a wave splashed him, it would start frantically glowing. As the waves increased, the "light show" became more and more active.

The Corinthian curse touched us, though it did not completely pass us by—for it caught up with us, of course, just when we least expected it, and in the very place we least expected it.

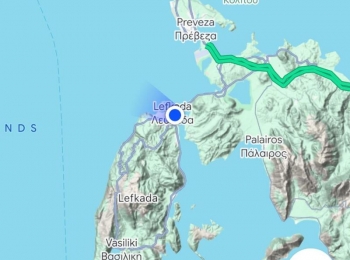

After several days of being stuck inside the Corinthian Gulf, we finally made it to Lefkada. But not long after we had set foot on land, right in front of a restaurant, Feridun tripped on the pavement and twisted his ankle—and not half a minute later, in the very same spot, Özgür fell as well, flat out, all the length and weight of him.

We couldn’t quite tell whether it was Apollonius’s prophecy at work, or simply the endless loyalty of friends—in good times and in bad—falling one after the other.

And speaking of loyalty—despite some grumbling from various crew members about our captain’s decisions, at sea the order is clear: the captain must be obeyed, even when wrong. And that might as well be the hardest aspect of life at sea.

If that code weren’t so deeply engraved in maritime culture, we would have seen far more mutinies—like the one on the Bounty, when the crew, enchanted by life in Haiti, chose to overthrow their captain and stay behind.

Antikyra almost became our Haiti.

Antikyra is a small fishing village on the coast near the famous temple of Delphi, where mooring at the pier costs just 10 euros, water is free, and cheerful locals catch sea bass using bait made from bread mixed with fish scraps on a simple rod.

On top of that, the wonderful people of Antikyra helped us solve Nikša’s constant craving for high-calorie food with their phenomenal gyros.

Although we swore that after that brutal night we wouldn’t move until every wind had died down—even if it meant spending the whole winter in Antikyra—we still left and sailed just under 20 miles northwest to Nafpaktos, also known as Lepanto, or as our Turkish crewmates call it, İnebat.

Nafpaktos is a strategically important mainland town whose rich history has been written by many—first by the ancient peoples, then by the Venetians and Ottomans, and now by modern Greeks—all thanks to its position at the mouth of the Gulf of Corinth.

As always with Başak and Ömer, people seem to materialize out of nowhere—a wonderfully random mix you’d never bump into in the sterile elevators of our office towers.

In Nafpaktos, two more characters drifted into our merry little circus for a day and half a night: Ozan, a Turkish captain, and Caitlyn, a Canadian hostess—both crew on an Israeli yacht conveniently anchored right between Pero and Soledad.

Our new friends not only gave us hours of laughter and salty sea tales, but also spoiled us with luxury transfers in their plush dinghy—ferrying us from boat to boat and back to shore in style. Ozan, who has crossed the Atlantic more times than he can count, seems to have been everywhere, and every one of his stories could easily fuel a sitcom about sailors and life at sea.

When the time came, we said our goodbyes to Caitlyn and Ozan, promised to reunite soon, and, as is proper in the 21st century, sealed it all by following each other on Instagram. Then, slipping under the famous Rio–Antirio Bridge, we left Nafpaktos behind and set our course for Lefkada. On that stretch of roughly 80 nautical miles, we really put Pero through the wringer—trying out every possible sail configuration, including the spinnaker, which is rarely and painfully deployed. Rarely—because the winds seldom call for it, and painfully—because when something is done so rarely, it inevitably feels difficult. Still, at Nikša’s relentless urging, we hoisted our Valentino-red spinnaker, and just as we finally had it set perfectly, a fierce westerly wind picked up—forcing us to take it down again almost immediately.

I was secretly rooting for us to stop at Ithaca—Odysseus’s home, and symbolically too important to skip—but as the lowest-ranking crew member, I didn’t dare push my ideas. Not this time at least.

What I did impose, in my role as cabin crew, was that the moment we arrived in Lefkada, every piece of textile from the boat had to go straight to the laundry. Although we’d already had a round of hand—or rather, foot-powered—washing back in Antikyra, there were still countless salt-crusted T-shirts, pillowcases, and sheets waiting to be dealt with.

In the laundry, we left our Soledad Marine Textile T-shirts, covers, towels, and sheets and had the honor of encountering the Greek counterpart of the notorious Croatian (un)friendliness towards foreigners. A lady with the physique of a character straight out of the Brothers Grimm—holding not a broom, but an IQOS—was loudly scolding us in Greek: that we had too many things, that she didn’t want me giving her my phone number, and that everything would only be ready by 7 PM and cost 120 euros. We accepted without complaint—because otherwise, she might well have tossed us into the sea.

Around 6 p.m., on the way back from the showers, the big bosses—Özgür and Feridun, each in his own field—spent a long time debating whether it was too risky to stop by and see if it might already be done.

In the end, they opted to send their envoy, Nikša, who returned triumphantly signaling that the mission was accomplished. We quickly loaded our precious cargo into the cart and hurried back to the ship to proclaim the news of yet another battle won.

In the meantime, the crew of Soledad—namely Ömer and Arif—had a “run-in” with the mythical laundry beast, who turned them away at the door. Defeated but undeterred, they set off again, hauling some 20 kilos of dirty laundry through the city until they stumbled upon a self-service laundromat hidden deep in its interior.

Their effort paid off—if nothing else, they came out of it far better off financially. 20 euros compared to our 120.

The evening in Lefkada was spent with two seasoned sailors, Catay and Veli, who had stopped over while coming from the opposite direction. They had set off from Portorož to deliver a super-luxury Hanse 510 sailboat, purchased by a client of the company Trio Marin, where both of them work—not as skippers, but as managers. The client had requested the yacht be delivered to Marmaris.

The two of them sailed from Slovenia to Lefkas Marina on Lefkada with only a single five-hour break at Vis—yet, like true gentlemen, always with the wind at their backs.

I hope you have enjoyed this 5th episode of the Soledad Sailing Challenge 2025 chronicles you can find the other episodes in English and in Croatian at this link.

And if you are interested in abridged romanticized biographies of the crew, you can find them here.

Photographic evidence can be found in the gallery below the text.

Video gallery

#SoledadChallenge2025 #soledadmarinetextile

Soledad Sailing Challenge 2025 - #1 Entry

Bodrum to Kos sailing #sailing #travel #kos #bodrum